WITH most students trying their best to juggle deadlines, money worries, relationships, part-time work and more, it’s unsurprising that mental health issues are becoming more widespread across universities in the UK.

As more young people are diagnosed with a mental illness, such as depression or anxiety, a higher amount of pressure is put onto the support staff employed by universities to deliver a satisfactory and personalised duty of care.

At the end of last year, ambitious Salford University student, Samantha Macdonald, 20, tragically committed suicide.

Inquiries revealed that the hardworking biology student had recently received lower grades than anticipated in her exams and “may have been secretly fighting an undiagnosed bout of depression”.

The inquest also heard that she had never sought help for mental health issues from a doctor or university health advisor.

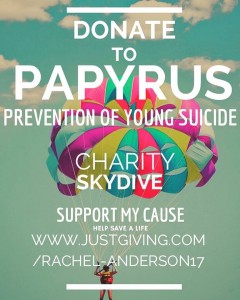

Affected by Samantha’s heartbreaking story, University of Salford student, Rachel Anderson, 21, organised a charity skydive in her memory.

“Mental health is still seen to be quite a taboo subject which many people avoid talking about.

“After learning about the work of my chosen charity PAPYRUS, I decided to take the opportunity to promote their work and raise money to help support their projects.”

Rachel explained how she had watched one of her closest friends struggle with anxiety for years.

She admitted it wasn’t until she spoke to her personal tutor about how she was feeling that she first found out about the services offered by the university.

“They offer help but only for those that have realised talking helps in these situations.

“By the time you do get to the point where you feel like you can ask for help, the waiting list to see someone is ridiculous.”

In a Depression Awareness Week 2016 survey undertaken by 100 students, only 61% said they knew of the services offered by their university to help with mental health or personal wellbeing issues, despite over 90% being diagnosed with a mental illness or knowing another student who had received a diagnosis.

Reacting to these results, Iain Pearson, a Wellbeing Advisor at the University of Salford, said:

“Since 2010, the number of students accessing support has grown. In many respects, that’s a really, really good thing, because students are more willing to come forward and stigma is going down.

“But at the same time, there’s clearly a need and it’s concerning that we’re unable to meet that need.”

“We’d really like to get that percentage up to just the odd few who don’t know about the service.”

Iain spoke of upcoming plans to get a lot more publicity out into the university itself.

“A lot of work with subject and personal tutors is needed to make sure that they feel much more prepared themselves to work with students around mental health.

“They also need to be able to confidently promote our service, our events and so on.”

Iain and his colleagues began running a series of workshops this academic year, which focus on coping with issues, such as anxiety and perfectionism.

“The turn out hasn’t been as high as we would’ve liked, but we’re working on it.

“One thing we’re looking to do is try to embed them within the different schools and get them out to university accommodation.”

Iain added that the feedback received from students regarding the services offered is “generally very, very good.”

With more advertising, greater collaboration with university tutors and integration into the curriculum, hopefully more struggling students will feel that they can reach out and access the mental health support that they need.

Recent Comments